TAKING A BATH

An intricate hand manipulates the roar

until the spout ceases, providing

only drips, a minuscule rhythm,

and steaming ripples are interrupted

by toes, feet, and then, an entire beast.

Inspiration, expiration: the level

of water shifts with the lungs

and soon sleep overtakes the creature.

Ripples, steam, drips: all continue.

Our man and the window perspire.

Salt-filled beads push through tight tunnels

and emerge from a taut face to soft light.

Released from epidermic passages

they scatter a mandibular stretch to the chin,

dangle, then leap with a microscopic yelp.

They hit the abdominal runway, and sometimes split

before wiggling off to waterline.

It is here that they become something other than alone.

Once submerged, molecular dialogue occurs,

rumors regarding pending demise, lost friends,

and hints of a nexus beyond this container.

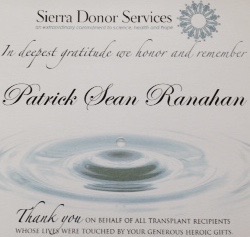

Patrick Ranahan

Published in

Latitude on 2nd

Cool Waters Media, Inc

2012

PATRICK'S LAST FACEBOOK POSTS

June 17: Have a lunch date today with my 96-year-old maternal grandmother, Evelyn Funk Moon. I treasure these lunches with her.

June 18: Ok, so I caved and did something I swore I was never going to do. I played Candy Crush Saga for like two minutes and now I'm being inundated with Candy Crush requests. Please folks, I doubt if I will every play that stupid game again.

June 21: My schedule doesn't really provide any days off. So six days a week I have to be ready for work. Some days are marked with a B for backup which means that you don't know until morning if you have to work that day until your phone rings. Makes it hard to plan things or get things done. Today is a backup day for me so I am praying that my phone does not ring this morning from dispatch. A day off would be much appreciated.

This is how smart I am: I got up this morning and emptied all of my garbage from the house into the garbage can outside. Then I got in my car and drove to work without putting the garbage can out for collection. So it will sit for another week:

Chris: At least you remembered to get the garbage in the can.

Pat: So I've got that going for me.

June 22: Let the dog in, let the dog out, let the dog in, let the dog out, repeat.

June 23: One of the best lines from the Mother Hips new album, Chronicle Man is, "You can't win, but you can feel good trying."

June 24: Why do I have to leave the toilet seat down, why don't you leave the toilet seat up?

Tanya: What??

Patrick: Girls vs. boys

Brandi: We pee and #2 sitting down, so majority rules.

Patrick: That sounds like a personal problem.

Brandi: So...You #2 standing up? You have the problem

Patrick: Equal rights ma'am.

Erin: Plus you had 3 sisters and no brothers. Majority rules again!!! And I guess it's worse to fall into a toilet than to have to lift. But I've wondered about this before haha!

Shawn: Question I've had for years.

Patrick: Yes, Erin, precisely for the reason that I had to suffer through a childhood full of crazy women and no brothers, I am entitled to the privilege of leaving the toilet seat up.

Shawn: I've never understood how anyone sits down on anything, including a toilet, without looking where they are sitting.

June 28: At pre-High Sierra Music Festival meeting last night, learned that our campsite will be equipped with an air conditioned RV with a full kitchen, a full drum kit, numerous guitars, and other percussion instruments.

July 1: If you're in traffic and you have the right of way at an intersection, you're not doing anybody any favors if you wave other cars to go ahead when you're the one who is supposed to go.

July 3: Going offline for a few days at the High Sierra Music Festival. Time to face the music.

Chris: Have a great time Patrick.

Geoff: The Music Never Stopped.

Patrick: For a while it never started.

Lisa: Have fun Pat!!

Beth: Have fun!

Donna: Have a great time!!!

July 6: Just had one of the most restful, refreshing nights of deep sleep I've had in a long while. Outside in a tent and sleeping bag on the cold hard ground.

July 10: My next band is going to be called "Boobs Make the Package."

AFTER THOUGHTS

I had no idea, of course, when I began writing in June 2013, that not only was I recording my 70th year, I was also recording the last year of my son's life. I had no intention of including a "Before" or "After" section of my book. And then events necessitated a change of plan.

On July 9, Pat called about Lexi. "Hi, Mom. I think I have to take Lexi back."

"Why? What did she do?"

"She's destroying the house. She's torn up the bathroom floor. I think the whole thing will have to be replaced. I've got an appointment at four o'clock to take her back to the SPCA."

Pat was crying. This made me cry. "I feel stupid crying," he said.

"No, no. It's okay. This is hard. This is sad. I'd be more concerned if you weren't crying."

"I phoned Dad to see if he could take her on his ranch. He said, 'no.' I've failed her. I've let her down."

"Pat, you haven't failed her. No one's tried harder with this dog. And it's not fair to her to be cooped up all day while you're at work. She needs to be outside in a big space where she can run around. You're making a really tough decision but it's the right decision. Give yourself credit for doing the right thing."

"I feel like I'm not doing anything right."

"Well, from the outside looking in, you're doing many things right. Do you want me to go with you to take Lexi back?"

"No, I want to do this myself."

"Will you call me when you get home from the SPCA?"

"Yes."

At 5 p.m. Pat called again. "Hi, Mom."

"How did it go?"

"It was awful. I had to fill out lots of paperwork and the lady kept asking me, 'Are you sure you want to do this?' And I found out they're not a no-kill shelter. If they can't place her they'll put her down. The woman asked me if I wanted to be notified if they decide to put her down. At first I said, 'no' but then I said 'yes.' I'd have twenty-four hours to try to find a place for her. The lady wouldn't stop with her questions and I was about to break down, so I left."

"Do you want to come over for dinner?"

"No, I think I want to be alone tonight."

"Don't forget to take good care of you."

"I'm trying, Mom."

I was afraid to go over to Pat's house, my mother's property. I suspected I'd find much more damage than Pat had told me about. Whatever damage there was, it could be handled later. My son's emotional well-being came first.

Pat had enjoyed a wonderful weekend at the High Sierra Music Festival, a festival he'd wanted to go to for a long time. On Friday, July 11, Pat stopped by my house. He'd squeezed his money every which way to make it to the festival. "Mom, I mailed a check for my car's DMV renewal. Can you loan me one hundred twenty-seven dollars to cover it until my next pay day?"

Pat talked about having trouble sleeping. "I went to the hospital emergency room a couple days ago to get sleeping medication and I had a terrible day at work yesterday. I keep forgetting things. I had to go back to the store three times to pick up the parts I was supposed to deliver. I think it's because I'm so upset about Lexi."

I noticed Pat's slacks were hanging off of him. "Are you losing weight?"

"Yeah, well, I didn't realize how much working full time and trying to take care of Lexi were going to take out of me."

I gave Pat a check and invited him to stay for dinner but he said he had to get home because a friend was coming by. Later that evening, Pat called. "I meant to ask you earlier, but I forgot. Do you think I should tell my boss at work about my bipolar disorder?"

"Why are you thinking about this now?"

"I don't know. Sometimes I feel like I'm not being honest."

"Do you remember, Pat, the last time you confided to a supervisor about your illness, you lost your job? Why don't you wait and think about it?"

On Saturday, July 12, Pat collapsed at work. An ambulance took him to the hospital where he received anti-seizure medication. In the evening, Pat called to tell me what happened.

"The hospital didn't want to keep you overnight for observation?"

"No, they told me to go home and rest."

"Pat, do you want me to come over?"

"No, Mom. I'm really tired. I want to go to bed."

On Sunday morning, July 13, I texted Pat and asked, "How are you his morning?"

He texted back, "Do you want me to call you?"

"If you want to. I didn't want to wake you if you were sleeping."

Pat never called. Sometime later that day, he was 5150d to the hospital in an agitated state of manic psychosis. The hospital didn't call to let me know about Pat's admission. I found out he was in the hospital psych ward when he called my brother, Jim. Pat had filled out an Advanced Care Directive listing Jim and me as his preferred contacts.

I hired a cleaning crew to clean Pat's house and a carpet cleaner. I wanted to see if something would salvage the carpet which reeked of dog urine. I picked up Pat's dirty clothes, towels, and bedding and brought them home to launder them. I bought a new frying pan to replace his old grungy one. I wanted everything to be as nice as it could be when Pat got back to his house. And I went to the SPCA to check on Lexi. She'd been adopted, already, by a couple who lived out in the country.

On Thursday, July 17, Kerry and I went to the hospital to see Pat. We didn't know how he would receive us. When we walked into his room, he was sitting up in a hospital bed with his wrists in restraints. He didn't look like the same person I'd seen the week before. His hair hung stringy and unwashed, and his face, pale and thin, was unshaven. His eyes gleamed wildly but he was glad to see us.

"Mom, the nurses don't believe me. You can tell them. Tell them I have a black half-brother."

My heart sank. After six days in the hospital, Pat was still delusional. I shook my head. "Pat, you don't have a black half-brother."

Pat was also upset because he couldn't find his wallet. Although we'd already been in his house to clean it, Kerry was concerned that he'd be angry when he found out we were there without his permission. "Pat," she said, "Do you want us to look for your wallet in your house?"

"Yes, that's a good idea."

The nurses were getting ready to move Pat onto a different floor. Kerry and I waited in the hallway until they wheeled his bed out of his room. As they pushed him away down the hall, I yelled to the back of his head, "I love you, Pat."

Without turning around, he yelled back, "Love you too, Mom."

Those were the last words we'd ever hear each other say.

Kaiser told us they would be transferring Pat to an outside psychiatric facility when a bed became available. It turned out, without our knowledge, they transferred him out of the county to Woodland Memorial Hospital - over 50 miles away. We found out where Pat was when he called Jim again.

Meanwhile, I was trying to get through to a doctor. Jim told a doctor who'd spoken him that I was also on Pat's advanced directive and it was okay to talk to me. But no one called. I called Kaiser Membership Services. Since Pat was no longer in their care, they said they couldn't help me. I called a number for Woodland Memorial asking to talk to Pat's doctor. I was told, "The doctor spoke with your brother. He doesn't have time to talk to everyone in the family."

On Tuesday, July 22, a woman called me from Woodland Memorial. She asked, "What is your discharge plan for your son?"

I lost it. "I have no discharge plan. No one has updated me on his status. What's happening with him?"

"Well," this woman said, "your son is very ill and needs long-term housing in a psych board and care facility. Does he receive disability to pay for his care? Do you know what medications have worked for him in the past?"

Now I was sobbing. "I don't know what worked for him in the past," I screamed. "I wasn't given that information. Don't you have his psych records from Kaiser?"

The woman wasn't sure. She said she'd check.

I hung up the phone. I could barely put one foot in front of the other. My legs felt like lead. All we'd worked for, all Pat had worked for was gone — his dog, his job, his independent living, his mind. How could he face all this loss when he came home?

Tuesday evening, Pat called Jim again. "Uncle Jim, they're killing people here. You have to help me get out of here. I have a car and a driver waiting behind the hospital. Help me get out of here."

Jim said, "Hang in there, Pat. We're working with your doctors to get you home as soon as possible. Do what your doctors say."

When I went to bed Tuesday night, I despaired. I said out loud to the walls, "I give up. I have no idea what to do."

Wednesday morning, July 23, as I sat at my kitchen table, the phone rang. It was a nurse from Woodland Memorial. "We're moving your son to the ICU. A doctor will call you shortly."

The ICU? What was happening? At last, a doctor was going to talk to me. Twenty minutes after the first call, my phone rang again. This time a doctor spoke. "I'm sorry, your son, Patrick, died fifteen minutes ago. We believe he had a seizure. We tried for thirty minutes to save him. I'm sorry."

I froze. My son wasn't hoping to die. He'd told me, when he was admitted to the hospital for a possible seizure that recent Saturday, the doctor gave him a prescription and directed him to go "down the hall that dead ends in double doors to the pharmacy." The phrase "dead ends" rattled Pat. "I couldn't wait to get home," he said.

After going round and round with Woodland Memorial for a week after Pat died, trying to get an autopsy and a toxicology report, the county coroner stepped in and took charge of the process. Six months later, the coroner's report would say the cause of death was inconclusive: "Possible seizure or possible cardiac arrest."

I could write more about the last few weeks of Pat's life, my frustration and anger with our mental illness system (there is none), and the drastic need for change — sooner than tomorrow. I'd make a case for effective, compassionate care for our seriously mentally ill. I'd point out tragedies that could have been prevented and the urgent need for beds and housing. I'd challenge outrageous HIPAA laws that prevent moms and dads like me from giving and receiving life-saving information. I'd talk about our missing and homeless children and mothers and fathers. I'd tell stories about our sons and daughters in jails and prisons and solitary confinement without treatment and on and on... My writing would turn into a tirade and that rant is for another time. Not here. Not on sacred ground.

When he died, Pat had one dollar and fifty cents in his checking account. The first day I went to pick up his mail, I found a postcard from a student at Hampshire College, his alma mater. The young man thanked Pat for a ten-dollar donation he'd recently made to the college.