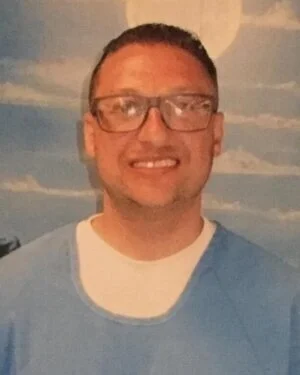

Yesterday, I drove to Ione, California to visit Travis Christian (BB8099) at Mule Creek State Prison. Travis is in solitary confinement for one-and-a-half to two years. He lives in a tiny, walled cell with a bed and some lockers. He’s allowed “yard” time three days a week — one half hour in an 8x10 foot cage. He attends “groups” a few times a week — again in a one-person cage. Sometimes the group watches a movie. Travis says they’re going to discuss stress management. (I’d like to know how to manage stress in solitary confinement 24/7.)

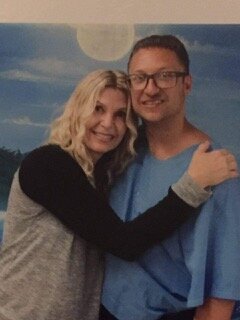

I’ve been visiting Travis once a month since October 2018. (You can read about my visits here.) I knew of Travis’ s mother, Kathy, through this blog. At first, Travis was in prison in Southern California, then he was transferred to Folsom, California which is about 45 minutes from where I live. Now, in Ione, the trip takes an hour and a half. Prison staff told Kathy that Travis was transferred because Folsom is over-crowded. A couple days before he was moved, a prisoner in Travis’s cell block hanged himself.

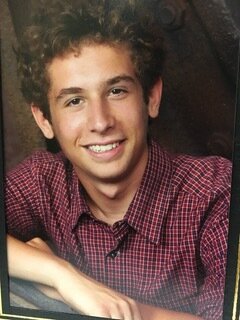

Travis originally went to prison for stabbing a man he thought was Satan. He ended up in solitary after punching a med tech he thought was Satan. Now he’s in trouble again for attacking his cell mate because he believed he was Satan. A recurring delusion. “I thought I needed to rid the world of evil,” Travis says. The back story, this time, is that Travis decided he was “fine,” went off his meds with prison permission (“It’s his right,”), and ended up in the prison hospital. Kathy had pleaded with prison staff to not take Travis off his meds. “We’ve been down this road before,” she told them, “and it always ends badly.” The staff said they would monitor Travis. So much for that. Now Travis is facing an attempted murder charge and many more years in prison.

When Travis walked into the visiting booth (he sat behind glass and we talked on a phone) he seemed dazed. He’d had no human conversation in over a week. He said, “I’m okay,” and then he teared up. “I’m being punished. They try to break you in here. Dede, sometimes I lose it. I want to give up.” As we talked, Travis began to relax. “I miss human conversation so much. Thank you for coming.”

Travis did have some good news. “Friday, I got over 20 letters — from all over the United States. I couldn’t believe it when the guard handed me my mail. ‘All this? For me?’ People wrote that they read about me on your blog. They said, ‘Hang in there. Do not lose hope.’ I was overcome. I broke down. I couldn’t read for a while. I couldn’t do anything.”

I asked, “Travis, when you’re feeling overwhelmed, can you ask to see your doctor?”

“No, Dede, it doesn’t work that way. I see my doctor once a week at a scheduled time.”

I told Travis his mom has ordered a TV for him and it should arrive in a week or so. “I’m counting on that TV,” he said. “To get my mind on other things. To feel more alive. I have to hold on until I get that TV. And my property. They haven’t given me my things from Folsom — some books and photos and stuff. I don’t know when they’ll give them to me.”

At times, each of us was quiet — trying to think of something positive to talk about. “All we have is this moment,” Travis said. “Let’s talk about now. How are you doing, Dede?”

As our visit came to an end Travis asked, “When are you coming again?”

“Travis, I’ll keep coming on the second Sunday.” Through the glass, I blew him a kiss.

On the drive home, I opened my car windows and sucked in the outside — the brown California grasses, the clusters of black oaks, the herds of cows and goats. I reflected on my visit with Travis. The prison felt surreal. Like the twilight zone. The guard at the motor entrance smiled and told me, “Have a good day.” The staff attendee in the visiting area was pleasant. He apologized that my 11 a.m. visit with Travis began one half hour late. A baby in a pink headband cooed on an inmate’s (her father’s?) lap. Couples hugged and bought hamburgers from vending machines. Children, polished and shiny, sat politely in family circles. Travis entered the visiting booth with his hands behind his back. He inserted them into a slot in the door to wait for a guard to remove the handcuffs. As he described his cell and his dreary routine, the juxtaposition of normal and bizarre jarred my body and my senses.

Travis is alone. Totally alone. One of many, throughout our country, who are isolated for days, months, and years. Anything could happen. Additionally challenged by his serious mental illness, Travis could lose the will to survive. He needs to know the world hasn’t forgotten him. Right now, I’m a connection. I’ll be there for him as long as I can be. He needs me, and you, and all of us.

At the end of the day, we’re lucky if we can help one person. One person at a time…

Travis’s mailing address:

Travis Christian BB8099

C-12-230

Mule Creek State Prison

PO Box 409060

Ione, California 95640

Travis intends to respond to everyone who writes to him. Sometimes he’s out of paper or stamps or envelopes. His writing tool is a pen filler — the internal part of a pen. The casing is removed. It’s difficult to write with the filler. Travis tries to wrap paper around it to make it thicker and easier to hold. “I’m still figuring out how to do this,” he says. You can send books to Travis but only by ordering and shipping them to him from Amazon. He’s reading a fantasy book right now because “It takes me out of here.”