Dear Senator Sanders,

This is in regard to your Disability plan, more specifically your plan to vigorously enforce the Olmstead Decision, and your support of the Medicaid IMD Exclusion.

As you know, the Olmstead decision is a 1999 Supreme Court decision which determined that people with mental illness should be treated in the least restrictive environment possible. I completely agree with that. What you are forgetting, or ignoring, is that the Olmstead decision was not to close institutions, but rather to make sure that only those who truly needed to be in one, were. Justice Ginsberg warned us to not close institutions when she wrote the following in the decision:

"The ADA is not reasonably read to impel States to phase out institutions, placing patients in need of close care at risk. Nor is it the ADA’s mission to drive States to move institutionalized patients into an inappropriate setting... Some individuals may need institutional care from time to time to stabilize acute psychiatric symptoms. For others, no placement outside the institution may ever be appropriate…This Court emphasizes that nothing in the ADA or its implementing regulations condones termination of institutional settings for persons unable to handle or benefit from community settings. Nor is there any federal requirement that community-based treatment be imposed on patients who do not desire it."

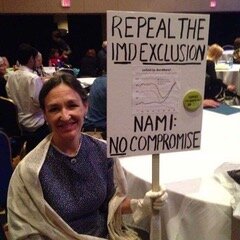

The Medicaid Institutes for Mental Diseases (IMD) Exclusion, enacted in 1964 when Medicaid was created, bans federal matching Medicaid funds to cover the treatment of otherwise Medicaid eligible adults being treated in a psychiatric hospital (or any facility over 16 beds that provides 24/7 nursing care to people with a mental illness and/or addiction). If you support the IMD Exclusion, you support federally sanctioned discrimination, and a law which has already caused an extreme psychiatric bed shortage and put those “in need of close care” at great risk.

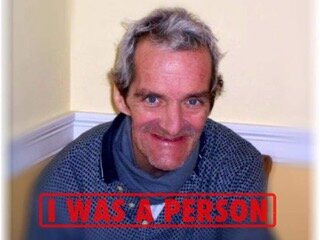

When my twin brother Paul was released from the New York State hospital system in 1998, after 20 years, many states were already off-loading patients into the community, whether or not they could handle or benefit from it, due to the financial squeeze from the IMD Exclusion. Paul was treated as if he were a fully functioning, fully recovered adult, yet he was permanently and gravely disabled and he never gained insight into his illness. Paul, our family, and members of our community, were traumatized by preventable incidents that occurred after his release, due to being placed in inappropriate settings, time and time again. He needed long-term care and pushing him into inappropriate community settings was detrimental to both his physical and mental health.

The Olmstead decision specifically states that a person should be treated in a less restrictive setting when the patient is clinically ready, willing, and there are appropriate setting and supports available. The first and third criteria are often left out of the equation today, with disastrous results.

The discriminatory Medicaid law and the improper enforcement of Olmstead have already been catastrophic to individuals, like my brother, who are in need of close care, their families, and the communities in which they live. They include re-hospitalization, re-institutionalization, homelessness, victimization, incarceration, and death. More people with a serious mental illness are institutionalized today than ever before, but they are in prison or in homeless shelters, not hospitals. This is a sad testament to the state of health care today for people with serious mental illness.

Proper support of Olmstead would include:

· Enough acute care and long-term psychiatric beds to support the treatment needs for our current population (approx. 50 beds per 100,000 adults)

· Assessment to determine appropriate treatment setting taking into account

· Whether or not the person has Anosognosia (lack of insight), which affects their ability to participate in treatment

· Level of existing symptoms

· Ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL) and overall cognitive functioning (Schizophrenia, for example, is a cognitive disorder that also affects memory and other cognitive abilities)

· Placement into a setting with supports built around assessment

· Housing to be both scattered and congregate as appropriate for the individuals needs

· Follow up after transition with mechanism to transition back to more restrictive environment, if necessary

· Further step-down to less restrictive environment only when criteria for that level is met

I urge you to re-think what it means to enforce Olmstead and to also support the repeal of the Medicaid IMD Exclusion.

Ilene’s brother Paul right before he died.